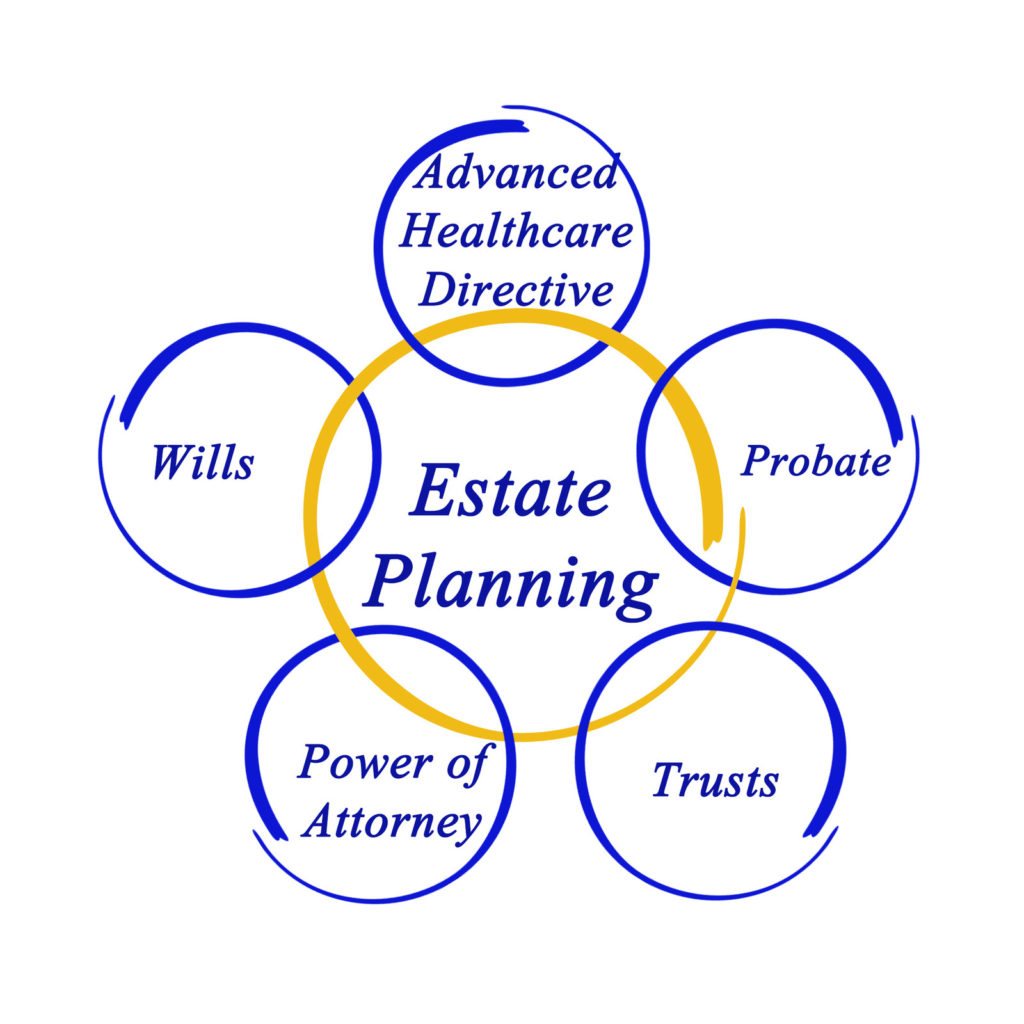

Thinking about guardianship and estate planning goes hand-in-hand with building your circle of support. Most individuals with Down syndrome will need financial and/or other supports in addition to what they can provide for themselves as adults. When your loved one is an infant, you can work with an attorney, and, perhaps, a financial planner to set up some legal documents, and begin considering how your family and your circle of support will address those long-term needs.

Childhood

Who will care for your child and make decisions for them, if you are unable? Who among your family and friends would you trust to love your child like their own, share your values with them as they grow and take over planning so that your child may experience a rich full life in adulthood?

Many families identify several people as potential guardians, so that if one person is unable to take responsibility when the time comes, the court can turn to the next person on the list. You should discuss your plans with those whom you would like to designate as potential guardians, and keep them informed about your child’s strengths needs and interests as she grows, so a transition from your care to the new guardian will go smoothly.

Adulthood

As your child approaches age 18, the question of guardianship changes from, “who should be my child’s legal guardian” to “does my child still need a legal guardian.” Until recently, parents were told that they MUST take guardianship of their disabled children when they turned 18. It was believed that individuals with Down syndrome would not know how to make decisions or understand the consequences of those decisions.

We know now that individuals with Down syndrome are able to live full, meaningful lives when given the opportunity and that with support they are quite capable of making good choices for themselves. They dream the same dreams about where to live, how to spend their money, and who they marry that we all do, for example, and those wishes should be respected.

“People with Down syndrome] dream the same dreams about where to live, how to spend their money, and who they marry that we all do, for example, and those wishes should be respected.”

While some families still choose full guardianship today, alternatives to full guardianship have become more common, allowing adults with disabilities greater independence and autonomy in the way they live their lives. Remember, if you take full guardianship at 18, full guardianship will then transfer to another individual or a court-appointed organization when you are no longer able to fulfill your responsibilities. In Connecticut, here are the options available to consider:

Full or plenary guardianship is when one person has control over all aspects of another person’s life – everything from when to brush their teeth to where that person can live. Full guardianship is so extreme that an individual’s needs are supposed to be examined in great detail to be sure full guardianship it is absolutely necessary. There is no guarantee, however, that a judge’s review will be thorough. Additionally, guardianship can be very difficult to change once it has been created, so we suggest you examine alternatives and consider carefully before electing to remove all your loved one’s decision-making powers.

Limited guardianship restricts the guardian to control of certain areas of life, such as finances or healthcare management. This is still restrictive and does not guarantee that the guardian will consider the wishes and interests of your loved one. Guardians – full and limited – typically have to submit reports to the court about the decisions they have made, but, again, there is no guarantee that the oversight will be thorough.

An evolving alternative to guardianship is called supported decision-making. It is intimately linked to an individual’s circle of support. People without intellectual disability use informal circles of support to make decisions all the time when they ask friends, family and trusted professionals for help and advice.

Have you consulted with your neighbor who loves gardening about how to plant trees in your yard? Did you seek help from your cousin, who is an attorney, when you signed the contract to buy your home? How many times have you asked a friend who rocks parenting for guidance in getting your son — the night owl — to stay in bed? If you have an answer to those questions or others like them, you have leaned on your informal circle of support. Individuals with intellectual disabilities like Down syndrome benefit from explicitly building similar social connections with long-term support needs in mind.

While Connecticut law does not yet specifically address supported guardianship, it is possible to create the arrangement of relationships, practices and agreements that helps a person with a disability understand, make and communicate decisions about their own life by drawing on examples and documents that are used in states where supported decision making is codified. See resources below.

Connecting Families

Connecting Families